Kelsey Milian

The City University of New York

(JSPS Summer Program 2024, Kansai Gaidai University) |

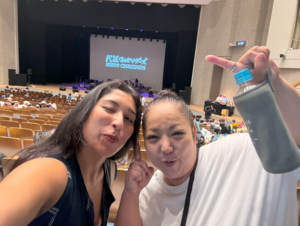

|

Boten no Hana in Hayama

I still dream about my first morning after waking up at the Sokendai University Campus during the August JSPS Summer Program 2024 orientation. I was battling intense jet lag from the previous days, so I decided to explore the Hayama area from where the university is located. I looked through my Google Maps and found a running route leading me to the beach and an overlook called Boten no Hana. A 45-minute walk that I turned into a 25-minute run. I grabbed my running sneakers, put on my headphones, and began blasting my playlist, a mix of Reggaeton and Japanese pop music. The sun was starting to rise, and the cool air seemed to cancel out the island’s intense humidity. I ran downhill through scenic homes of pastel hues and overlooks, where the soundscape of streams begged me to listen to the sounds of nature around me. The trickling of water buzzing with insects and the quiet hums of long roads. I ran through long tunnels that made me feel as if I were entering a different dimension once passing through. It was mind-altering to emerge onto the road, walk up man-made steps while hearing waves crash onto the rocks, and watch the sunrise brighten Mount Fuji in the distance. The orientation days were filled with Japanese cuisine, which I had fantasized about for years, and the camaraderie built upon a genuine curiosity of research interests, whether it be about language, water, trains, music, or physics. A group of us from the orientation would later come down the running path again to watch the sunset on Mount Fuji, across the waves, and with a certain eagerness for what would transpire throughout the summer, represented in that morning’s sunrise to sunset. On my last night of orientation, I sat on a balcony overlooking the university and listened to the murmur of the nighttime. I was optimistic and naive about the rest of the summer program, considering what I would learn and leave behind during such a unique and extraordinary experience. I applied to the JSPS summer program to conduct ethnographic research on Japanese spaces that may facilitate and share Latin American popular music, such as salsa, bachata, merengue, and especially reggaeton. My research involved attending specific clubs, bars, and restaurants that facilitated Latin American music in the Tokyo and Osaka scene nightlife. My host teacher and mentor, Dr. Flavin, and I were connected through our mutual field of Ethnomusicology. Dr. Flavin specifically studies Japanese traditional music, such as the Koto, and Japanese theater, such as Kabuki. As my host researcher, we often collaborated on the types of themes and questions I would generate through my fieldwork and developed plans to follow leads depending on where it would take me. Within Ethnomusicology, we are always interested in what music creation and sound can reveal about communities and cultures worldwide. I was lucky that my host university, Kansai Gaidai University in Hirakata, Osaka, was my alma mater 6 years ago as an undergraduate student. This experience was a homecoming of sorts, and I had the opportunity to walk the same streets, eat at the same Lawsons’, and walk the campus I used to when I was 21 years old. It also allowed me to reunite with friends I’ve been able to stay in touch with all these years. We would go to various listening cafes and go for evening runs at Osaka Castle to beat the heat of the summer! What started as an investigation of Japanese perceptions of Latin American popular music revealed various approaches toward sharing sonic elements of Latin American culture and identity in Japan. Specific Latin-American enclaves (physical venues), events, DJ collectives, and organizers have taken on “cultural bearer” roles in Tokyo and Osaka to share, educate, and raise awareness of a Latin-American presence within Japanese society. Music and dance are regarded as universal tools that transcend language barriers, in which rhythm and melody create sentiments and spaces of inclusivity. These experiences are curated and cultivated by a combination of “cultural bearers,” with a majority identifying as Latin American and Japanese citizens, explicitly taking on the professions of DJs, event organizers, and dance instructors. Navigating a world of speaking Spanish and Japanese, these DJs curate specific playlists for the various Latin events and collectives they participate in. Most stated that their primary goal is to expose Japanese people to Latin American music and culture and raise awareness of their multi-racial and multi-ethnic identities as Latin American and Japanese individuals. Of the DJs interviewed, the leading Latin American nationalities represented are Peru, Colombia, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Brazil, and Mexico. Historically, Japanese immigration to Latin America dates back to the 1880s, with some of the first Japanese colonies established in Peru and Mexico. However, this research identified three distinct categories or approaches to disseminating Latin American popular music within Japan: cultural enclaves, spectacles, and community events, which are split into open outdoor events and nightlife events. I did not have a chance to participate in the homestay program because my research working hours involved attending festivals and nighttime events during the weekends of the program. However, I still dived into Japanese culture and life, as my research allowed me to follow my primary informants and interlocutors in their everyday lives as entertainers, music creators, and participants in various activities throughout the region. For example, I saw my favorite band perform live with my DJ friend Miya. Miya is one of the only Japanese women DJing Latin American music in the city, and eagerly accepted my invitation to see the Minyo Crusaders when they were performing at the Musashino Civic Hall. This band takes on a unique approach to music as this 10-person band, composed of vocals, woodwinds, brass, and percussion, composes and sings entirely in Japanese while producing Colombian cumbia rhythms. I will never forget seeing a Japanese audience dance and sing so freely the rhythms of Colombian cumbias. It was more memorable that I had the chance to share the experience with my informant and friend. I cherished my time in Japan and intended to make the most of it. I wanted to center my experiences on genuinely learning and growing through my research experiences. I am grateful for all the people I met, and it was a learning lesson to fully embrace the opportunities and experiences, no matter the outcomes. |

MENU

Kelsey Milian

- HOME »

- Voice of a Former Fellow »

- Kelsey Milian

Car tunnel leading to Boten no Hana

Car tunnel leading to Boten no Hana Boten no Hana overlook with fellow JSPS colleague Maggie Reed

Boten no Hana overlook with fellow JSPS colleague Maggie Reed Kansai Gaidai University in Hirakata, Osaka, and my best friend, Maurice Kasahara

Kansai Gaidai University in Hirakata, Osaka, and my best friend, Maurice Kasahara Members of Colombia Alegra dancing at the Latin Festival in Yoyogi Park- July 6-7, 2024

Members of Colombia Alegra dancing at the Latin Festival in Yoyogi Park- July 6-7, 2024 DJ Ami and DJ Miya Tequila at the Latin Festival in Yoyogi Park- July 6-7,2024

DJ Ami and DJ Miya Tequila at the Latin Festival in Yoyogi Park- July 6-7,2024 DJ Miya and I at the Minyo Crusaders concert in Musashino Civic Hall

DJ Miya and I at the Minyo Crusaders concert in Musashino Civic Hall