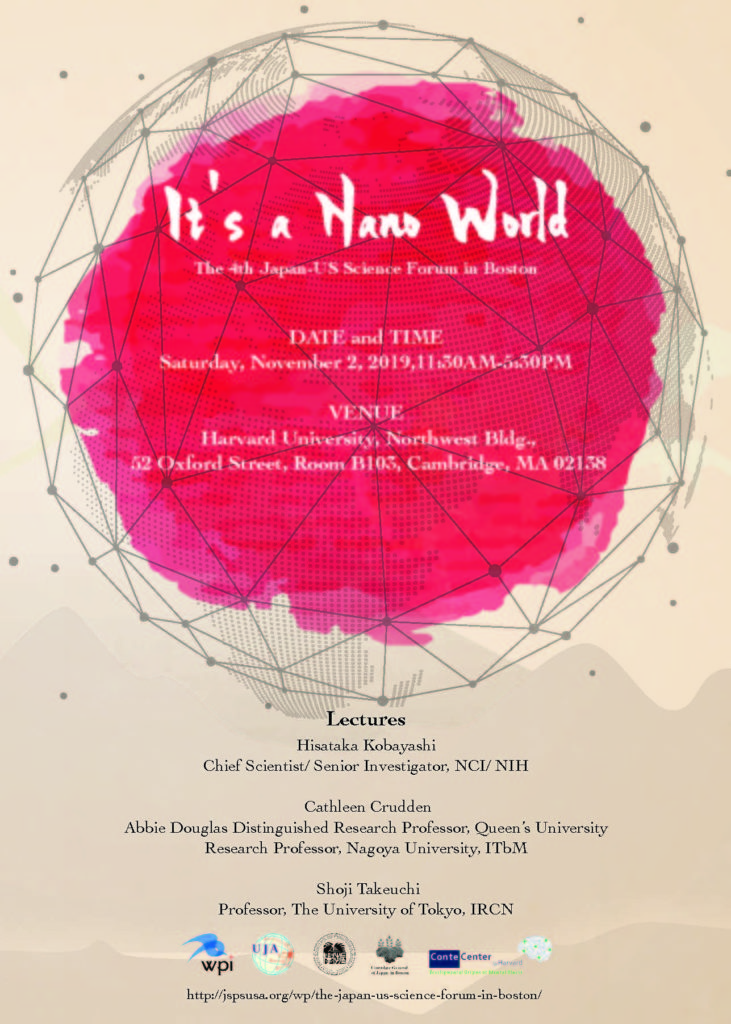

“It’s a Nano World” [Nov. 2, 2019]

BOSTON (Nov. 2, 2019) — Sometimes, scientific discoveries that can have a huge impact on society come in tiny packages.

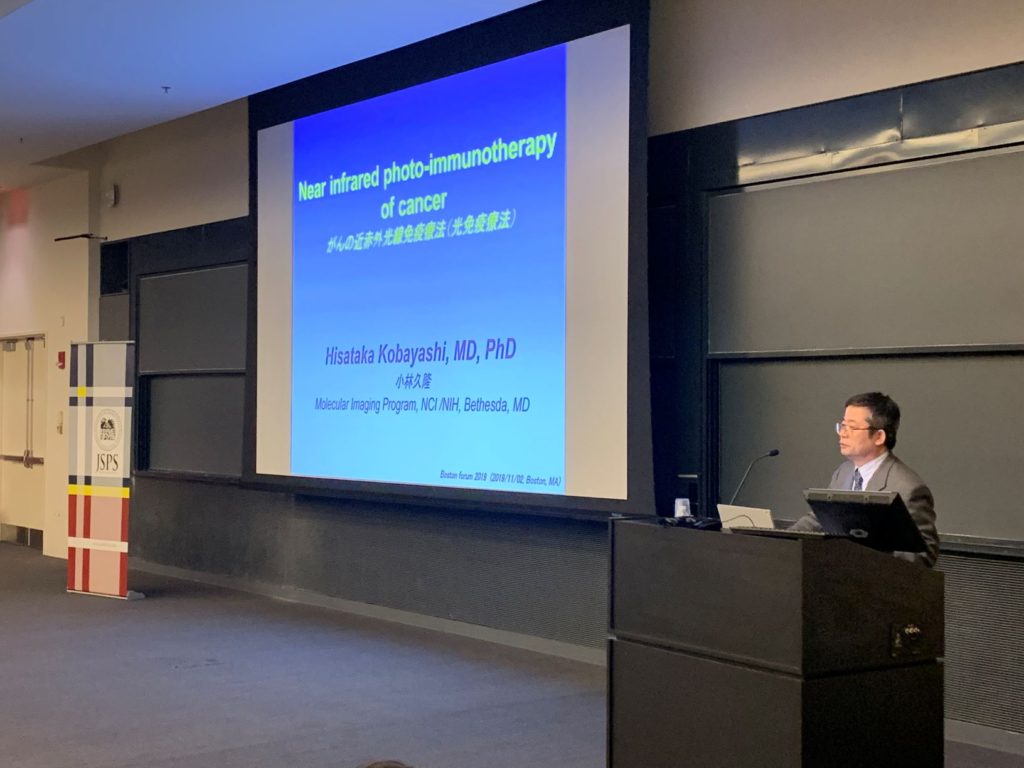

Photoimmunotherapy, a novel cancer treatment developed by Dr. Hisataka Kobayashi and his team at the National Institute of Health (NIH), for example, causes tumor cells to explode by beaming near-infrared light at special dye bound to antibodies that are 100,000 times smaller than a short rice grain. Nano-sized molecules also play critical roles in a biohybrid mosquito’s olfactory sensor that Dr. Shoji Takeuchi and his team at the University of Tokyo Institute of Industrial Science developed in hopes that it will someday help find humans, just as search dogs do, in rescue missions.

These breakthroughs — both of which were presented at the 4th annual Japan-US Science Forum in Boston, held Nov. 2 at Harvard University — demonstrate what’s possible with nanoscience and innovative applications of it. But they are also a testament to the cross-disciplinary collaborations among researchers from around the world, Drs. Kobayashi and Takeuchi told the forum audience. Dr. Kobayashi, for one, moved from Japan to work at NIH for its large pool of potential “good collaborators” for his project. Working with people who speak different scientific languages enriches the mind, Dr. Takeuchi said.

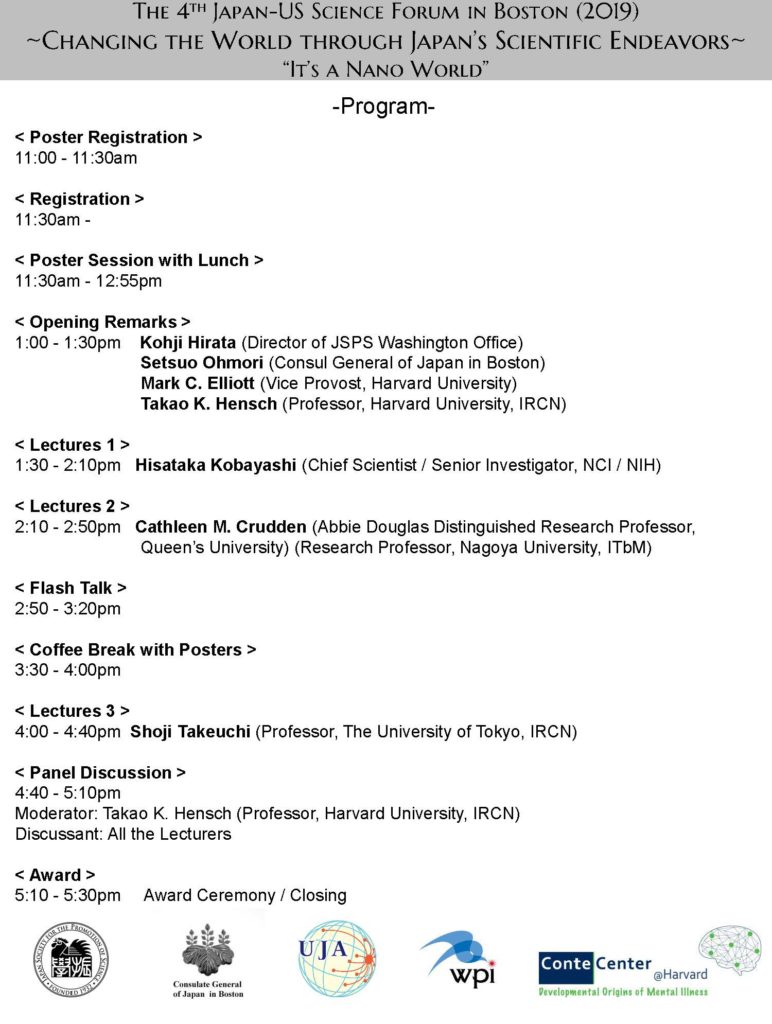

For the fourth year, the Science Forum brought the American and Japanese science communities together in Boston, providing scientists from both countries and elsewhere with the opportunity to exchange ideas and inspiration. Taking the theme of “It’s a nano world!” this year’s event featured keynote lectures by Drs. Kobayashi and Takeuchi, both of whom are globally renowned for their groundbreaking discoveries involving nano-scale matters. Prof. Cathleen Crudden of Queen’s University of Ontario, who was scheduled to give a lecture on nanoparticles’ implications in chemistry and biology, could not attend the forum due to the flooding in her region.

Jointly organized by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS)’s Washington Office, the Consulate General of Japan in Boston, and the United Japanese Researchers Around the World (UJA), the forum began in 2016 as a way to showcase Japan’s scientific undertakings and promote global partnerships. With a large number of leading technology and bio- and life-science labs and companies clustered in a one-mile radius near Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University, Boston is a fitting location for the forum, said Setsuo Ohmori, Consul General of Japan in Boston, in his opening remarks.

The forum’s goal is to change the world through science, according to Dr. Kohji Hirata, director of the JSPS Washington Office. And achieving it requires scientists to surround themselves in diversity, said Harvard University professor Takao Hensch, who moderated the forum.

“Being a scientist today means being a kokusai-jin (‘worldly person’ in Japanese),” Dr. Mark Elliott, vice provost of Harvard University, said, as he opened the annual forum that aims to foster global scientific collaborations. “You cannot do science in one country any more.”

“Learning from other cultures and having different perspectives prevents you from getting stuck in a rut,” Dr. Hensch said.

Dr. Kobayashi Develops Therapy That Cures Cancer Without Causing Any Harm to Patient

The biggest problem with conventional cancer therapies, Dr. Kobayashi said, is that they always leave some cancer cells behind while reducing the body’s ability to fight the disease. That’s because surgery, radiation and chemotherapy all destroy or damage healthy cells along with cancer cells, compromising the patient’s immune system.

Even cutting-edge immunotherapy, which weaponizes one’s immune system against cancer, isn’t the perfect solution to the problem. It doesn’t always wipe out all the cancer cells nor work in every patient.

Dr. Kobayashi’s quest for a better way to treat cancer paid off in the form of the innovation of near-infrared photoimmunotherapy (NIR-PIT). This revolutionary cancer therapy “selectively crushes cancer cells without damaging any normal cells,” according to Dr. Kobayashi. What’s more, cancer cells release antigenic content when crushed, activating the body’s defense system to kill off all the remaining cancer cells elsewhere in the body. This makes the patient immune to the disease, as well, preventing a recurrence of the particular cancer for which they were treated. The therapy has already cured patients of advanced head and neck cancer in a clinical trial.

Photoimmunotherapy’s power lies in the combined use of monoclonal antibodies (mAb), which bind to specific cancer antigens, and IR700, a non-toxic photo-absorbing dye that Dr. Kobayashi’s team discovered to have a lethal effect on cancer cells only when exposed to near-infrared light. In treatment, the antibody-dye compounds are injected into the patient, which then travel to the cancer site and bind with tumor cells. Once the compounds are exposed to near-infrared light through the patient’s skin, it activates the chemical chain reactions that cause damage to cancer cells’ membranes. Water then floods into the cancer cells through the damaged membranes, causing them to swell and eventually blow up from the internal water pressure.

“This change is very, very quick,” Dr. Kobayashi said of the chemical and physiological domino effect triggered by light exposure.

The effect of the therapy is felt just as quickly. In a late-stage cancer patient in a clinical trial, the tumor cells turned white and began falling off the day after the treatment. While light is applied on the tumor area only, the treatment works for the entire body.

“Even though it’s a localized therapy, the patient can be cured and survive longer. That’s the trick of the therapy,” Dr. Kobayashi said.

All the while, all the healthy cells adjacent to the cancer cells remain intact, Dr. Kobayashi explained.

The antibodies used in the therapy measure 13 nanometers-long and 10 nanometers-wide. (One nanometer is one ten-thousandth the diameter of a human hair.)

“My technology is not in fact nanotechnology, but this is an applied product from many different nanotechnology bases,” Dr. Kobayashi said.

Dr. Takeuchi Brings Together Best of Technological and Biological Worlds in His biohybrid devices

Dr. Shoji Takeuchi believes robots and living things don’t necessarily have to be each other’s antonyms. Instead of trying to overcome the tremendous challenges of artificially replicating the functions of biological systems, such as those of muscular systems, one could incorporate the biological systems directly into synthetic ones, he said.

And Dr. Takeuchi has done just that since when he was in college, successfully inventing biohybrid devices of all sorts, including the world’s first robot complete with a biohybrid “nose.” It was developed as an alternative for search dogs, whose peak performances only last for 15 minutes on average at a time, according to Dr. Takeuchi. He thought about a mosquito’s antenna that detects the presence of octenol — odorant chemicals in human sweat — from the electrical signal produced in the cells when octenol molecules pass through cell’s gatekeeper, membrane proteins. Only 10-nanometers long, membrane proteins are biological systems’ sensors, he said.

“The problem is that the amplitude of these kinds of signals is very, very low,” Dr. Takeuchi said. “So, the problem (in building an artificial odor sensing system) is how can we detect the very tiny signals coming from the receptors?”

To work around the problem, Dr. Takeuchi and his team decided to use nature’s system as is, by creating lipid bilayer and implanting the membrane proteins found in a mosquito’s antenna in it. When an individually wrapped bilayer is placed in a device designed to measure the electrical balance between both sides of the bilayer, an odor can be detected. This biosensor can tell the differences among similar odors that are indistinguishable for artificial odor sensors.

The bilayers can be kept frozen until used. The system could be used to detect spoiled food, blood glucose levels in diabetic patients and for many other purposes by simply incorporating different kinds of membrane proteins, he noted.

For the robotic muscles, his team cultured tissues from hydrogel sheets containing myoblasts — or, early muscle cells — and anchored them to a 3D-printed synthetic skeleton. The muscles would contract and expand as electrodes are applied to them, making the skeleton’s joint fold and extend, just as a finger or arm would, to manipulate an object.

Back in 2013, Dr. Takeuchi and his team also developed a method to culture tissues in the shape of a rope by hardening tissue cells and collagen in a tube. This method could revolutionize regenerative medicine, as being able to three-dimensionally layer short strands of living tissues measuring several dozens to several hundred micrometers in length is key to regenerating complex organs, such as liver and pancreas. Grafting tissue fibers that are cultured this way helps prevent the patient’s body from rejecting them, according to Dr. Takeuchi. Stem cells are also more likely to take root when cultured via this method. And because tubes remain in that form, they could be pulled out, as well.

“If the patient’s body doesn’t like it, we can retrieve it,” he said.

Panel Discussion Focuses on How to Be Effective Leader in Global Research Community

If you are a young scientist looking for a way to be successful, Dr. Kobayashi said, you should try to carve out a specialty of your own. You may then become a pioneer of a particular research area.

“Seek your own interest and vision,” he said. “Successful PIs (principal investigators) have a unique identity in their own science (fields),” Dr. Kobayashi said in response to an audience member’s request for career advice during the panel discussion that followed the keynote lectures.

One’s ability to make friends and collaborate with a diverse group of people is also a key, Dr. Takeuchi said.

“Nowadays, research cannot be done by a single person,” he said. “You need to respect people coming from different research areas,” just as much as you respect researchers in the traditional science fields, he said.

Moderated by Dr. Hensch, the panel discussion with Drs. Kobayashi and Takeuchi took the form of a question-and-answer session. The topics discussed ranged from career development to research funding to the real-world applications of technologies. Dr. Takeuchi noted that the cycles of public grants in Japan are becoming shorter, making it difficult to conduct long-term research. Dr. Kobayashi commented on how venture capitalists play crucial roles in creating innovation in the U.S. by investing in startups. In Japan, funding from private sectors is hard to come by for ambitious start-ups, Dr. Takeuchi said. Corporate funding for research organizations, such as universities, also tends to be limited in the amount and scope, but both sides usually have friendly, collaborative relationships, according to Dr. Takeuchi.

Poster Session Brings Together Innovative Minds from Around Globe

This year’s forum featured Flash Talk, a segment in which each of the 28 poster session participants made a one-minute oral presentation with the use of PowerPoint slides. The presented projects ranged widely in fields of study from infectious disease to astrophysics.

The presenters included current and past fellows of the JSPS, which is Japan’s largest public funding agency for academic activities. The event organizers judged the poster presentations as a contest, bestowing special awards upon three of the presenters in the following categories:

- Consulate of Japan Award: Matthew Julius (Department of Biological Science, St. Cloud State University) for his presentation titled, “Marine-inspired biosilica 3-D printed bioresorbable scaffolds for bone repair”

- JSPS Award: Joji Kusuyama (Joslin Diabetes Center, Harvard Medical School), for his presentation titled, “Identification of a novel placenta-derived protein that mediates the beneficial effects of maternal exercise on offspring liver”

- UJA Award: Wataru Katagiri (Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital) for his presentation titled, “Real-time imaging of vaccine bio-distribution zwitterionic NIR nanoparticles”

The Consulate of Japan Award, the JSPS Award and the UJA Award were presented to the recipients by Mr. Ohmori, Dr. Hirata and Dr. Akinori Kawakami, a UJA board member, respectively.

Many participants of the poster session said they look forward to the Science Forum every year, as it provides them with a rare opportunity to meet researchers from other disciplines.

“I’ve made connections, and we’ve become friends. We ask what each other is doing from time to time,” said Kanako Bessho-Uehara, a current JSPS fellow and postdoctoral fellow at the Carnegie Institution for Science, relating how she and those whom she met at a past forum have remained in touch.

Both poster presenters and other forum attendees said forming such casual friendships with fellow researchers is invaluable to them, as it can engender inspiring conversations — and potentially even lead to research collaborations.

Shinya Yokomizo, Ph.D. candidate at Gordon Center for Medical Imaging, Department of Radiology at Massachusetts General Hospital, said hearing what is actually going on along the front lines of cutting-edge research from the keynote speakers was inspiring.

Yusaku Hontani, a current JSPS fellow and postdoc fellow at the School of Applied and Engineering Physics at Cornell University, was particularly interested in Dr. Kobayashi’s project that uses a photochemical, as he conducts research on photochemistry in the context of optogenetics. He appreciated the opportunity to learn from the lectures about how scientific discoveries can be turned into useful technologies.