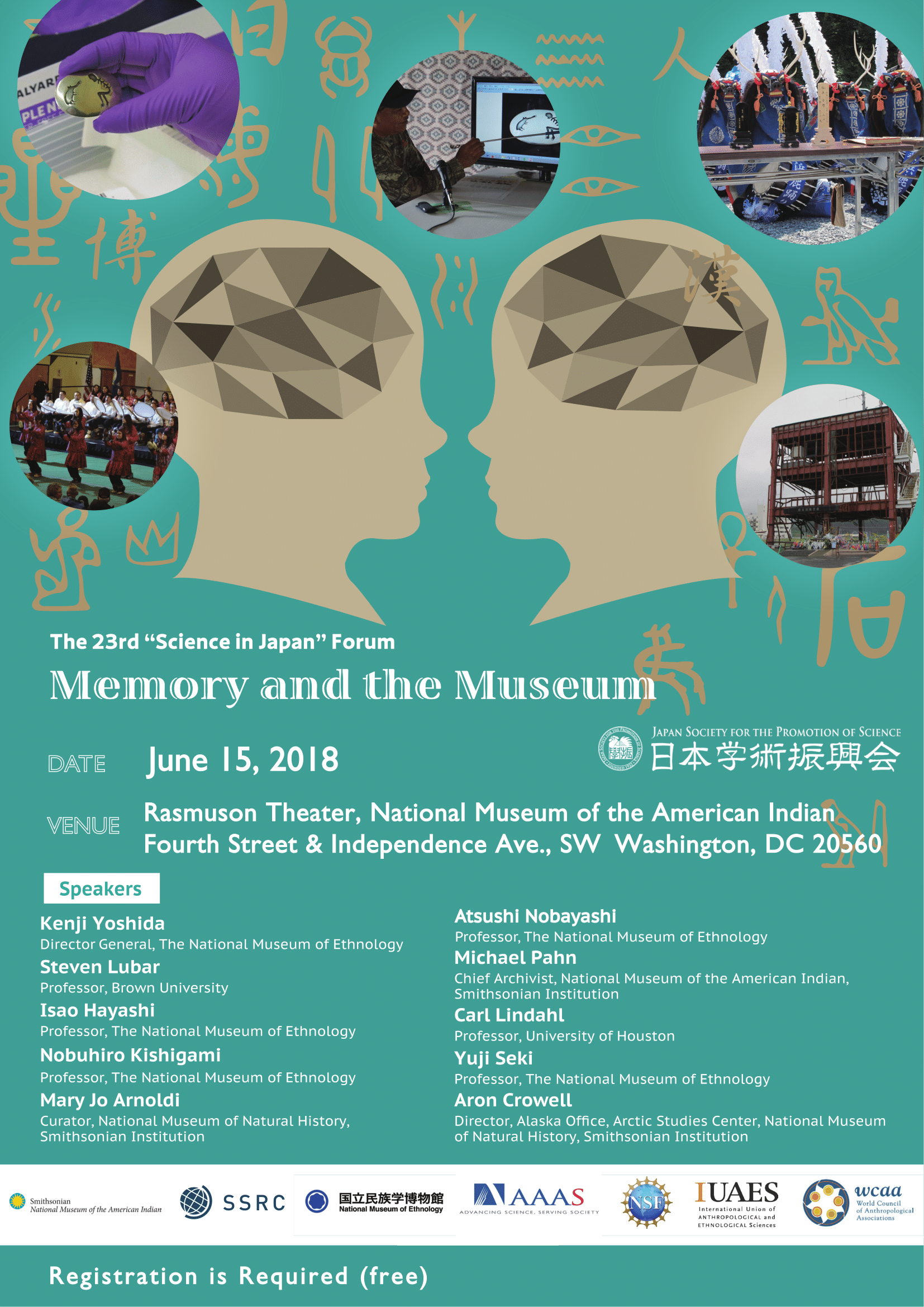

Science in Japan Forum 2018

On 15 June, the JSPS Washington Office held its 23rd annual “Science in Japan” Forum, venued this time in the Rasmuson Theater at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, D.C. Located on the National Mall, NMAI was established in 2004 as the first national museum in the US dedicated exclusively to Native Americans. Themed “Memory and the Museum,” the event featured special lectures from American and Japanese speakers on such topics as the role of objects in preserving memories, how museums and ethnographers can support communities affected by natural disasters, and exploring ways to ensure that communities have an equal voice in designing exhibitions that portray their cultures. The speakers included five members of Japan’s National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku), and experts from NMAI, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), Brown University, and University of Houston. Approximately 100 people attended this full-day event, comprising a mix of museum curators, professors, students, and interested members of the public. Several attendees were participating in a JSPS event for the first time, drawn to the forum by its attractive topic. The audience actively engaged the speakers in discussions during the Q&A sessions and breaks between the speaker sessions.

From left to right, Ms. Machel Monenerkit (the deputy director of the NMAI), Dr. Kohji Hirata (the director of JSPS’s Washington office), Ambassador Kazutoshi Aikawa (the deputy chief of mission at the Embassy of Japan in Washington).

The forum’s opening remarks were delivered by JSPS Washington Office director Dr. Kohji Hirata, NMAI deputy director Ms. Machel Monenerkit, and Ambassador Kazutoshi Aikawa, who is currently serving as the deputy chief of mission at the Japanese Embassy in Washington, D.C. Dr. Hirata introduced the forum’s program and emphasized the importance of the humanities as a cornerstone of science. Ms. Monenerkit welcomed the event attendees to NMAI, and described new exhibits at the NMAI that are fostering scientific and artistic knowledge as a whole, such as the museum’s “Great Inca Road” exhibit and the imagiNATIONS Activity Center at NMAI’s New York facility.

In his remarks, Ambassador Aikawa spoke about Eliza Scidmore, an American writer, photographer and geographer who became the first female board member of the National Geographic Society, who recorded the devastation from an 1896 earthquake in northern Japan, telling the story of the suffering, healing, and resilience of the people of the region. Scidmore later pushed to plant Japanese cherry trees in Washington, D.C., leading to the planting of about 3,000 Japanese cherry trees around the Tidal Basin and on the Capitol grounds. Ambassador Aikawa reminded the audience that the National Cherry Blossom Festival in Washington, D.C., the biggest spring celebration to commemorate the gift of Japanese cherry trees in the U.S., needs determined people like Eliza Scidmore to ensure that the friendship between Japan and the U.S. lasts the test of time. He hopes that the memory of Japan’s response to the Great East Japan Earthquake will inspire people who are struggling with difficult times in other parts of the world.

Keynote Speech #1: Prof. Kenji Yoshida, Director-General, The National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku)

Prof. Kenji Yoshida (Director-General, The National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku))

Prof. Yoshida introduced the National Museum of Ethnology (“Minpaku”) and its research staff and collection. He then spoke about his view that museums are facing their first important turning point since the establishment of the British Museum in 1753, as they are changing from places for the preservation and exhibition of objects of the past, and are becoming places to meet and transmit their collective and individual memories across generations. Prof. Yoshida emphasized that memory is not a thing of the past, but of the present, which connects the past and future as an essential part of identity.

According to Prof. Yoshida, until recently, museums presented information from the perspective of the “central” group, compared with “peripheral” groups such as indigenous peoples. However, this one-sided structure of interaction is being revised into bilateral interactions. Prof. Yoshida cited as an example how museums in the host cities for the Olympic Games have often faced criticism for presenting information without consultation from indigenous people, but over time, the Olympics have become opportunities for indigenous people to showcase their culture and speak about local problems. In 2020, Japan will host the Olympics, and plans to open the National Ainu Museum just before then.

Minpaku hosts an annual traditional Ainu ceremony, called Kamuinomi, using objects kept at the museum, which helps the museum to serve as a forum for the Ainu culture. Minpaku has also held workshops with Zuni people, where they have handled historical Zuni artifacts and interacted with the memories provoked by them. Many of the Zuni participants said that they participated so that the information could be provided to their children. Prof. Yoshida sees these as examples of how the museum can be a custodian for collections, where people can meet and conduct collaborative work.

Outside of the forum, Prof. Yoshida mentioned that most U.S. museums began as private collections, so people in the U.S. have usually felt comfortable adapting the museums to use for their own purposes over time. In contrast, the first museums in Japan were founded by the Imperial family, so most people felt some personal distance between themselves and the museums. Now, the major task for many museums in Japan is to reduce the distance between them and their audiences, so that they can become a space for people to come and interact with each other.

Prof. Yoshida also noted that he hopes that the JSPS forum will lead to the possibility for future collaboration between Japanese museums and U.S. museums, following up on several joint projects between Minpaku and the Smithsonian Institution in the past. Prof. Yoshida believes that often the best opportunities for bilateral cooperation can be created through developing personal bonds between researchers, which can then naturally lead to holistic/formal collaborative agreements that will support enduring ties between institutions.

Keynote #2: Prof. Steven Lubar, Brown University

Prof. Steven Lubar (Brown University)

Prof. Lubar spoke about how objects interact with memory, stating that “In their birth, life, and death, objects hold memories, and serve as a memoir to recalling the past.” Prof. Lubar considered three broad types of objects that hold memories: objects that are born to hold memories, such as a patchwork quilt; objects that have acquired memories through use as touchstones of past events, such as worn-out clothing or repaired ceramics; and objects that have acquired meaning after their usage, such as heirlooms, or preserved ruins.

Prof. Lubar described the study of Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO), which puts things at the center of the study of existence, and ponders their relationship with ourselves. Prof. Lubar argued that objects are interesting, revealing, provocative, and useful, especially old and broken things, since they hold memories, capturing the world around them in ways that are obvious and not so obvious. Indigenous museums and post-colonial museums in particular have led the way in presenting objects as living entities, moving beyond why things were made to also consider how they were used.

Prof. Lubar asked the audience to consider what it might mean for museums if they were to take OOO seriously, and thought about objects as “compressed time,” that can teach us about their egos, memories, and stories of trauma. Taking objects’ lives seriously means taking curatorial work seriously, and means interpreting and reimagining and recreating histories, and considering the interaction of visitors’ stories and the objects’ stories.

Outside of the forum, Prof. Lubar noted that many anthropology museums around the world work together, which reflects how anthropological studies are naturally global in scope. Prof. Lubar mentioned that he sees all museums as sharing the same problem: finding ways to tell good and interesting stories using artifacts. There are many opportunities for museums worldwide to work together and learn from each other, especially when they are covering similar topics, such as in the two sessions that followed Prof. Lubar’s talk on how museums in the U.S. and Japan have worked with the survivors of natural disasters. Prof. Lubar is fascinated by the potential for museums to explore online experiences for visitors by digitalizing collections so that museums in countries like Japan can share their collections around the world. He noted that Japan in particular has some remarkable experiential museums where most of the collection is experienced through interactive screens.

In discussions during the breaks at the forum, several attendees said that they originally came to the forum because they were particularly interested in the topic of objects and memories, and said that Prof. Lubar’s talk helped them to think about how different objects can acquire meanings to different groups.

1st session, History & Memory, Speaker #1: Prof. Isao Hayashi, the National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku)

Prof. Isao Hayashi (the National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku))

Prof. Hayashi spoke about the relationship between the remembrance and records of the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011 and museum activities. He participated in a team from Minpaku that worked to salvage and provide reconstruction support for tangible and intangible cultural properties affected by the disaster.

Prof. Hayashi’s focus was on the folk performing arts, which were affected by the losses of members of performing arts groups who were killed or injured, as well as the damage to performance sites such as shrines, and damaged or lost clothing and props. In one case, Prof. Hayashi helped Shishi-Odori(Deer Dance) performers replace their traditional costumes that used deer antlers, working with hunting associations and venison processing firms to locate suitable antlers for the costumes. The performing group then performed memorial dances in honor of the dead from the disaster. He said that thinking about the cultural traditions in the afflicted Tohoku regions and the remembrance of the deceased and the prayers for their repose would be one of the focal points in a museum display on the impact of the earthquake, and a monument for them would be erected near the museum facilities.

1st Session, History & Memory, Speaker #2: Prof. Carl Lindahl, University of Houston

Prof. Carl Lindahl (University of Houston)

Prof. Lindahl spoke about his experiences in collecting oral narratives from survivors of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Over 1 million survivors were rendered homeless, and many came to Houston without relatives or possessions. Prof. Lindahl drew on his research on folklore and on how small, old-fashioned communities shared narratives together to propose the “Surviving Katrina and Rita in Houston” (SKRH) project, working with the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress and the American Folklore Society to create an oral history of the disaster that reflected the survivors’ experiences in their own words. SKRH provided free training and employment for more than 70 survivors to record and archive the stories of their peers, creating an ‘insider history’ of the disaster. The program was found to have positive effects on survivors’ emotional health, and led to a parallel program in Haiti in 2010.

In Prof. Lindahl’s view, the project shows how museums can give control of the narrative to the survivors. He noted that he had spoken with Japanese ethnologists such as Koji Kato and Yoko Taniguchi, who had found that objects and spoken words could be used effectively as healing tools for disaster survivors, by giving the survivors opportunities to reconstruct in their own words the communities that existed in their memories. In the Q&A session, Prof. Lindahl mentioned that he was impressed by how the Japanese ethnographers were excellent listeners for the survivors, and how their work was exceptionally good in helping survivors to heal themselves.

2nd Session, Body & Memory, 1st Speaker: Prof. Nobuhiro Kishigami, the National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku)

Prof. Nobuhiro Kishigami (the National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku))

Prof. Kishigami spoke about the traditional dances of the Inupiat people, an indigenous people in northwestern Alaska that is well known for their bowhead whale hunters. Whaling remains a central core of modern Inupiat life and culture, and the Inupiat conduct several festivals and feasts related to the whale hunts, which include drum dances. The whaling activities function as an ethnic symbol of their identity and “Eskimo-ness”, and the dances themselves are a means for the Inupiat to memorialize history in a broad sense, including personal, family, and collective experiences, as well as historical events.

The “Inupiat Heritage Center,” a local museum in Barrow, the Inupiat’s largest town, has large rooms where the Inupiat drum dance groups can practice and perform. By providing a space for the dance group performances, the local museum plays an important role in the continuation and promotion of the dance culture, and in transmitting the Inupiat memories across generations.

2nd Session, Body & Memory, 2nd Speaker: Dr. Mary Jo Arnoldi, Curator, National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), Smithsonian Institution

Dr. Mary Jo Arnoldi, Curator (National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), Smithsonian Institution)

In her presentation, Dr. Arnoldi described Mali’s puppet masquerades and how the tradition provides an important public context for shared identity. The masquerade performances are major social events that include dances, masks, and puppets, usually in the open spaces of the village. A troupe’s local identity is very important, such as a farmer group or a fishermen group, since each group has a distinct style of dancing, singing, and drumming, and song styles, which young people begin learning in childhood, and continue learning through youth groups.

The messages communicated in the performance are about how artistry and morality are inseparable: the performers’ ability in dancing is seen as a reflection of their moral character. During the Q&A, Dr. Arnoldi described each generation of performers as competing with the previous generation, so they can only win their reputations by surpassing their elders. In closing, she asked the audience members to consider how museums might ever be able to capture the richness of the masquerade tradition.

3rd Session, Things & Memory, 1st Speaker: Prof. Atsushi Nobayashi, the National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku)

Prof. Atsushi Nobayashi (the National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku))

Prof. Nobayashi works with the indigenous people of Taiwan, and spoke about a collaborative exhibition on their culture that he developed for Minpaku. The museum hosts a collection of Taiwanese materials that were collected during the Japanese colonial period, which are periodically shown during special exhibitions. In 2014, Prof. Nobayashi created an exhibit at Minpaku on the significance of craftwork for the indigenous people, which demonstrated how the crafts provide continuity in daily life and are contributing to a cultural revival. Prof. Nobayashi asked weavers from the indigenous community to create entire traditional woven costumes for display at Minpaku. The exhibit was created in collaboration with the indigenous people, and was a medium for the handcrafts experts to better understand their ancestors.

The handcraft experts also did a public workshop and met with Minpaku’s collection director and students. The experts expect Minpaku to store their works, and to support the next generation of indigenous people in Taiwan in creating new works. Prof. Nobayashi also created an online database platform for the Taiwan collection materials in English, Japanese, and Mandarin, so that Taiwanese stakeholders could easily access the online materials.

3rd Session, Things & Memory, 2nd Speaker: Mr. Michael Pahn, Head Archivist, National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), Smithsonian Institution

Mr. Michael Pahn (Head Archivist, National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), Smithsonian Institution)

Mr. Pahn spoke about NMAI’s work to engage with community members and its work to return museum pieces that were taken from communities in the early 20th century back to the community. He spoke about how NMAI worked with John Garcia, a citizen of the Santa Clara Pueblo, to identify some photographs of his family that were part of NMAI’s collection. Garcia’s great-great-grandfather, Oyi-tsa (Duck White), had been photographed by the famous photographer Edward S. Curtis in 1905, and Garcia shared with NMAI about how his family remembered him, and how many of Oyi-tsa’s descendants have honored his legacy by serving in leadership positions in the tribal government to the present day. Garcia helped the museum to learn more about many of its photos of the Santa Clara Pueblo, providing details about family members and homes in photographs that had previously lacked any context from the Pueblo community, and the additional information is now stored in NMAI’s online database.

NMAI’s work with Mr. Garcia was an example of how museums can serve as a repository of living culture, where people can come to learn about themselves and their history. Mr. Pahn noted that historical memories like Mr. Garcia’s are opportunities to overcome racist stereotypes, by transforming images of archetypes to photographs of fellow human beings. He encouraged the audience members to think about how museums’ databases will support future histories, making them increasingly accurate and better at supporting social justice.

4th Session, Community & Memory, 1st Speaker: Prof. Yuji Seki, the National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku)

Prof. Yuji Seki (the National Museum of Ethnology (Minpaku))

Prof. Seki has worked as an archaeologist in Peru for over 30 years, and spoke about how he has worked with two rural communities in developing the narratives about their cultures. In one case, his team found a gold burial site in Kuntur Wasi, which is the oldest such site that has been found in the Americas. However, the artifacts at the site created a problem, since many different organizations claimed ownership over them, both federal and local. This led to the decision to host the pieces in a museum in the village near Kuntur Wasi. The pieces were brought to Japan for an exhibition to raise funds, and then the museum was built in 1994. It was the first Peruvian museum run by peasants, and the museum started taking on an educational role in the community. The museum is a good example of how the local community has been empowered to speak about its culture through a symmetric relationship with the experts on Prof. Seki’s team.

In another case, Prof. Seki’s team has been excavating the tomb of the “Lady of Pacopampa”, and the local village held a parade recently to celebrate the village’s history, commemorating important events such as the time of the Incas and the arrival of the Spanish. Performers dressed as Prof. Seki and his team were a part of the parade, which he sees as a reflection of the relationship of power between the archaeologists and the people, who view them as leaders. According to Prof. Seki, the parade was an example of how social memory is flexible and is formed through the repetition of activities.

4th Session, Community & Memory, 2nd Speaker: Dr. Aron L. Crowell, Alaska Director, Arctic Studies Center, National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), Smithsonian Institution

Dr. Aron L. Crowell (Alaska Director, Arctic Studies Center, National Museum of Natural History (NMNH), Smithsonian Institution)

The focus of Dr. Crowell’s presentation was on oral traditions and how they interact with history. He described several oral legends by Alaskan indigenous peoples that described actual historical events such as a famine or volcanic eruption. He concluded that oral history can bring in the local people’s views on events, filling in areas of the narrative that archaeology cannot do.

During the Q&A session after his presentation, Dr. Crowell described how “there is always a dance between tradition and new elements or creativity, which can radically change the presentation,” as stories lose their specificity over time, crossing certain thresholds in which they lose clear details and acquire mythological elements, or lose their connections to a specific historical event.

In a discussion during a break at the forum, one attendee mentioned that she was particularly interested in learning about the oral traditions in Dr. Crowell’s presentation, since his insights were directly applicable to her own work in designing museum exhibitions to explore and present the history of a diverse neighborhood through narratives from multiple perspectives.

Panel Discussion – All Speakers

Panel Discussion

In the panel session, the speakers animated the discussion with a give-and-take of views that crisscrossed the forum’s topics in ways that riveted the audience’s interest and sparked a short but highly spirited Q&A discussion.

The panel began with a question by Prof. Yoshida to Prof. Lubar about his view on museums. Prof. Lubar commented that museums need to move beyond being “places that store objects” to capture performances, record oral histories, and capture the reactions of the communities, as a place where many different kinds of people are meeting.

Prof. Hayashi and Prof. Lindahl shared some of their thoughts about the objects that survivors of natural disasters carried from their homes. Prof. Lindahl noted that most survivors participating in the oral history didn’t bring up objects often, though his friend who participated in the rescue efforts for trapped survivors kept a tin of the Vienna sausages that was left over from the food that they passed out to survivors.

Prof. Lindahl also noted that in oral traditions about natural disasters, even though the details of the natural disasters were often lost over time, the messages about how to save oneself from the disaster were preserved. Prof. Hayashi brought up a story about a small community on an island which only had 7-8 people killed in the 2011 earthquake and tsunami out of a population of 800, because they had an oral tradition with a song about past tsunamis that everyone in the community knew: “When you feel earthquakes, don’t go to sea, just run to higher ground.” The simple song helped to transfer knowledge, and helped members of people to remember what to do in the short warning time that they had before the tsunami reached the community.

The panel also discussed the importance of developing databases that are accessible to community members, such as in Prof. Nobayashi’s work with the Taiwanese indigenous people. Mr. Pahn stated that there is a need now to think strategically and deliberately about how to ensure a path to moving data into the future, in order to keep up with new technological innovations.

Prof. Yoshida closed the panel discussion by suggesting that over the long term, museums should collaborate with schools to preserve ideas and history, and reminded the participants about the power of narrative, and the need to consider more productive or powerful ways to develop or restructure museums.

After the forum, several members of audience remained to further discuss the forum topics with the speakers. The speakers met on the following day to consider whether to produce further outputs, such as a report or publication, or to launch collaborations stemming from the forum’s discussions.

AAAS(American Association for the Advancement of Science),

IUAES(the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences),

NMAI(National Museum of the American Indian),

Minpaku(National Museum of Ethnology),

NSF(National Science Foundation),

SSRC(Social Science Research Council) and

WCAA(World Council of Anthropological Associations) are acknowledged for the co-sponsorship.